So much for shop talk, here is the data.

You know His methods, use them.

Concluding words of the Forward [sic] to W.T. Rabe’s

Sherlockian Who’s Who & What’s What,

The Old Soldiers of Baker Street: 1961.

Jon Lellenberg & Peter Blau

In 1961, Wilmer T. Rabe produced the first edition of Who’s Who & What’s What for a Sherlockian world prepared for and in need of it. This was a decade into a remarkable, roughly five-decade career as a Sherlockian and Baker Street Irregular that encompassed ten times the activity of the average Irregular. For “average” Bill Rabe was not: he was unconventional, made the most of it, and to those of us who knew him, is unforgettable.

Rabe was born in 1921, and hove into Sherlockian view in 1951 while serving in the U.S. Army’s psychological operations service in Germany, work for which his future affairs would show he was eminently suited. After returning to civilian life, he made a career at the University of Detroit as an “academic publicist.” Eventually he retired to Sault Ste. Marie on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, at the Canadian border, and soon had a new life there as the official island historian of nearby Mackinac Island, dubbed by him “the Miami Beach of the North,” and as press agent for its historic and majestic Grand Hotel.

Rabe was imaginative, and had a talent for making madness respectable, like serving as chief telephone book critic for the Detroit newspapers, and Detroit Hatchetman of The Friends of Lizzie Borden. At Lake Superior State University later on, he was a founder of The Unicorn Hunters: preferring Unicorn Questors because, he claimed, you shouldn’t hunt what you can’t find — but that did not stop him from issuing tens of thousands of unicorn hunting licenses.

Up on Mackinac Island he invented and also saw gleefully to the publicizing of an International Stone-Skipping Tournament, a World Sauntering Day, and other annual events of like madcap nature, including the custom of ceremonially burning a snowman on the first day of Spring. Caring about culture’s struggle with noise, he created Hush Records whose big hit was an original cast recording of “An Evening with Marcel Marceau.” Caring about language, he launched an annual List of Words Banished from the Queen’s English for Mis-Use, Over-Use, and General Uselessness, still issued on New Year’s Day by Lake Superior State U. (This year’s banished words: viral and Facebook/Google used as verbs.) He scorned bureaucracy, claiming to have once filed an income tax return filled out entirely in Roman numerals. He liked laughter, and was an enthusiastic member of The Sons of the Desert, the Laurel & Hardy fan club. And he loved Sherlock Holmes, so he became a Baker Street Irregular.

Not surprisingly, he began by creating his own society while in the Army, The Old Soldiers of Baker Street, or Old SOBs. He was in fact still young at the time; the photo below was taken when he visited the brand-new Sherlock Holmes Klubben in Copenhagen, entering Klubben legend by showing up with the first bottle of Scotch the thirsty Danes had seen since before the war. When he returned home from the Army to Detroit, he joined The Amateur Mendicant Society there, founded by Russell McLauchlin a few years before. Edgar W. Smith, a good judge of character, invested Rabe in the BSI in 1955 as “Colonel Warburton’s Madness.”

Bill Rabe with The Sherlock Holmes Klubben’s A.D. Henriksen (l.)

and Verner Seeman in Copenhagen on January 5, 1952. On the table is

the bottle of Vat 69 Rabe brought with to the Klubben dinner.

Over the years, Rabe’s contributions to Sherlockiana were legion. Among other things, he installed the first Sherlockian plaque at the Englischer Hof in Meiringen. He put out The Commonplace Book, a periodic compilation of newspaper and magazine articles about Sherlock Holmes and his followers. He tape-recorded memorable moments at BSI dinners and other events, issuing them on a set of records called Voices from Baker Street, now available on compact disc from Wessex Press. He became interested in James Montgomery’s extracanonical song “Aunt Clara,” tracked its multiple versions and long-lost origins to a songwriter’s alcoholic Christmas haze in 1936, and set forth its history and folklore in a splendid and profusely illustrated volume entitled We Always Mention Aunt Clara.

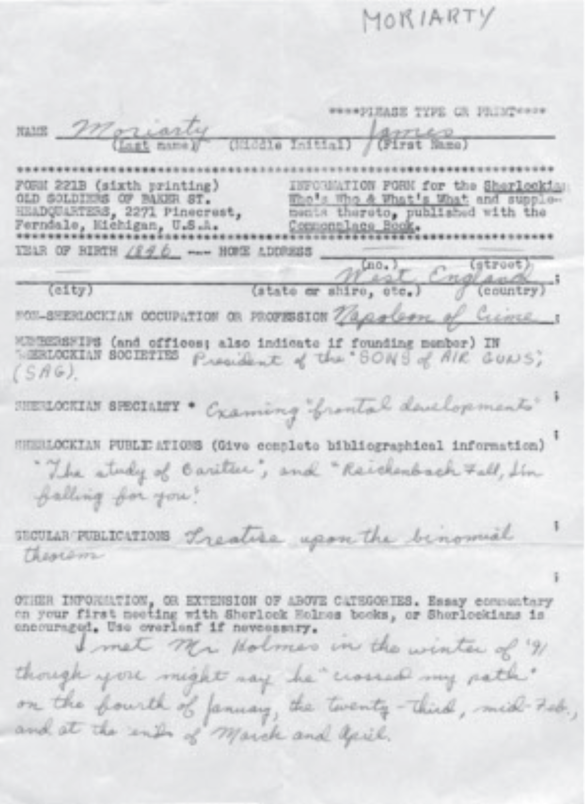

This last, the fruit of pensive nights and laborious days, is generally taken as Bill Rabe’s magnum opus, but rivaling it for that honor is something else he created fifty years ago which Sherlockian scholars and the Irregular historian continue to turn to and find useful: his ambitious Sherlockian Who’s Who & What’s What, a reference work published by The Old Soldiers of Baker Street in 1961 and sub-titled For the First Time Anywhere, Everything About Everybody Who is Anybody S’ian and Anything That Is Even Remotely H’ian, However Far Removed.

In its 122 softbound pages, Part I listed and described Sherlockian sites, plaques, periodicals, and other topics; Part II covered the Sherlockian societies; and Part III “The Followers,” with half a dozen appendices of additional data about Sherlockians and societies. The usefulness to the curious then and the historian today can be suggested by the mid-sized entry for E.W. McDiarmid, the University of Minnesota professor who was later a guiding light for its Sherlock Holmes Collections:

McDiarmid, Errett W. (1909- )—— 2077 Commonwealth, St. Paul 8, Minn.; college dean, U. of Minn.; NE (founding member, Sigerson, 1948- ); BSI (Bruce-Partington Plans). Speciality: the great hiatus; “Reichenbach and Beyond,” BSJ Christmas Annual, 1957; S.H.: Master Detective, The Sumac Press, 1952; Exploring S.H., The Sumac Press, 1957.

NE standing for Norwegian Explorers, described in the book’s societies section in terms of its founding, officers, milestones (including a plaque at the Reichenbach, with its own entry and photograph elsewhere in the book), publications, “habitat,” and, to use the term in the questionnaire Rabe sent out to Sherlockian societies, its singularity — which in the case of The Norwegian Explorers read as follows: SINGULARITY: Coed and “etc.” (ED. NOTE: ? )

Less “just-the-facts-ma’am” examples include some puckish entries like Doyle, Adrian Malcolm Conan (1910- )—Founder of A.C.D. Protective Assn., or the confused and confusing ones for Helene Yuhasova and Lenore Glen Offord, the first of said ladies erroneously described as a one-time pen-name for the late Edgar W. Smith, the second as having been “struck from the rolls,” so alleged on the authority of S. Tupper Bigelow of Toronto (“The Five Orange Pips,” BSI). This hideous libel led, in the next edition, to an appendix containing an irate letter from the well-known science-fiction writer and Scowrer Poul Anderson, “The Dreadful Abernetty Business,” BSI, who had witnessed Ms. Offord’s investiture at the hands of Edgar W. Smith himself, plus an exchange of letters between Anderson and Bigelow with the latter blaming the error on slipshod BSI record-keeping and promising to be careful in the future.

For the historically minded, one of the book’s particular usefulnesses lies in the many “small ‘i’ irregulars” included by Rabe, men and women not invested by the BSI but keeping the Memory green in their own ways: people who otherwise could scarcely be identified at this late stage whenever their names pop up in some old BSJ or scion publication. What Rabe called W4 has solved many a nagging mystery, and its usefulness is far from exhausted.

But as intended, Who’s Who & What’s What was extremely helpful fifty years ago to those who wanted to know about the Sherlockian world in an era when there were only two journals with any significant circulation, and no Internet. To cite but one example, Rabe was the first to try to compile a comprehensive list of Investitured Irregulars, as well as an informative survey of Sherlockian societies, something (Blau speaking here) no one since him has seriously attempted, let alone accomplished: my lists are fairly comprehensive, but hardly informative. And Rabe’s Commonplace Book was the first attempt to give wider circulation to what was appearing in the general press.

The Internet makes this all too easy today, but in those days just about the only other information came from squibs by the editors in the BSJ and SHJ. The Sherlockian world of the 1960s was quite different from today’s — in many ways quite parochial, as it wasn’t easy to participate in meetings of far-flung societies, and quite difficult to know much if anything about Sherlockians one hadn’t met other than in the BSJ’s Whodunit section. It was grand in 1961 to be able to learn about the people in the Who’s Who, and about the societies in an era when very few not members of local societies received the newsletters published by some of them.

People did not talk about the importance of Who’s Who & What’s What. That was pretty much taken for granted by those who acquired and valued it, with rather little attention paid to it in the Sherlockian press — not that there was much Sherlockian press in 1961. Julian Wolff barely mentioned it in the BSJ, essentially just announcing that it was available, and it is unknown how many copies were sold. Let alone survived; and it’s difficult to find copies in pristine condition, because Who’s Who & What’s What wasn’t something to be carefully shelved, but consulted frequently instead.

Yet it’s hard to overstate about how different the early 1960s were from today. Those who’ve grown up in the eras of Xerox, inexpensive long-distance telephone service, computer word processing, email, and Google can scarcely imagine what it took to research and bring out a work like this in 1961. It wasn’t easy to obtain information of all sorts in those distant days, and Who’s Who & What’s What, for many, was a new and wonderful way to get information about the Sherlockian world. It was in fact to foster a sense of community, more than anything else, that prompted Bill Rabe to undertake this project. Edgar W. Smith, who had been so much for so long not only to the BSI, but Sherlockians broadly, had died in 1960, and Who’s Who & What’s What was undertaken because of that. When it appeared the following year it was dedicated to Smith, with a touching dedicatory essay by Russell McLauchin saying in part:

What shall a lonesome friend say about a man who, with a matchless pen in his hand and an unquenchable joy in his bosom, did more to make sound and perpetual our Sherlockian fellowship than all the members of that fellowship, gathered and combined? He would have loved this book and hailed its author. And those two verbs might be interchanged, with unaltered accuracy. . . . There was much fear, when Edgar died, that our communion’s single, indispensable factor had departed; that all Sherlockian fellowship, with the animating spirit now grown still, might swiftly falter and soon expire. Probably the best word to be said about this volume is that it quite extinguishes such fear.

Not that Rabe was now content. In the first place, he believed in an expanding Sherlockian universe, and was conscious of the book’s incompleteness: “The majority of the entries have been either written by, or drawn directly from Forms 221B.2 completed by the S’ians concerned,” he explained in his Forward [sic], and “I have a feeling that I have overlooked many distinguished deceased S’ians, as well as their more lively colleagues; that I have asterisked scions into inactivity which are very active; and that there are probably itchy-fingered artists who were just waiting to be asked to draw caricatures of their distinguished associates.”

But in the second place, he was already looking ahead as he sent the volume to press, adding: “It is hoped that all these matters will be set right in the 1962 WW&WW, known in abbreviated military terminology as ‘62W4.” That did come out the following year, and after a while he planned for a third edition come 1968. But it was not realized. He had acknowledged his reliance upon the technical resources of his university employer: “Text typed by a charming, patient and understanding young lady, Miss Nancy Kelly, on a Royal Electric Executive Typewriter which adds considerable status to the correspondence of the University of Detroit Public Information Dept., as does Miss Kelly. Display type and assorted illustrations stolen from wherever we could find them. Printed on a University of Detroit imported (a good, though not a great year) offset press under the personal supervision of Dick Masserang,” and so on. When Rabe retired in 1967 he lost those resources, the PC-based era of self-publishing was not yet at hand, and four crammed jumbo three-ring binders in which he had been collecting data for the ‘68 edition went into a cardboard box stored in the attic of his new home in remote Sault Ste. Marie.

There they gathered dust some twenty years. But it is an old maxim of mine (Lellenberg speaking here) that no research ever goes unutilized. When the BSI Archival History got started, Bill swooped upon its first two volumes eagerly, reviewing the second enthusiastically for the Summer 1991 BSJ. Then he went up to his attic, found the old carton with those four jumbo binders containing the raw material for the 1968 Who’s Who & What’s, and shipped them to me. The data they contain facilitated the Archival History volumes that followed, and those shabby and precious binders continue to sit on a bookshelf in my study where I consult them frequently today. Bill Rabe’s Sherlockian Who’s Who & What’s What was and remains a great accomplishment of permanent value.

This article appeared in the September 2011 issue of the University of Minnesota Libraries’ Friends of the Sherlock Holmes Collections newsletter, edited by Julie McKuras, and won the Bryce Crawford Award for best contribution in that year’s quarterly issues. The issue in its entirety is at https://www.lib.umn.edu/pdf/holmes/v15n3.pdf.